Science fiction war – wonder weapons in the Second World War

Miracle weapons

Before and during the Second World War engineers developed a whole range of weapons, each representing a technological milestone. The following list, which makes no claims to be comprehensive, is in the chronological order of the system’s operability. All named developments were technically combat ready and were actually deployed, except the guided air-to-air and ground-to-air-rockets.

Note on the atomic bomb

The famous German physicist Heisenberg failed, others (Diebner, Gerlach etc.) successfully developed the atomic bomb. The German nuclear weapons used less than critical mass of Uranium. Instead, they utilised the very accurate pinpoint implosion of opposed hollow charge explosives to drive a plasma pinch at the fissile core. Thus, the Germans were capable of building much smaller (i.e. tactical) nuclear bombs than the US. They never used them. However, there were several German nuclear test explosions, on the island of Rügen as early as 12th October 1944, on 3rd and 12th March 1945 near Ohrdruf. After two frustrating years of futile research the USA still had no working ignition method at war’s end in Europe. The Germans did! The US were appalled. They stated that German technology was 100 years ahead of them. Of course, the US used what they had confiscated.

- Radar and radio measurement technology (Germany and Britain, later USA. Less sophisticated devices were developed by USSR and Japan)

- Ground-to-ground rockets (unguided) (USSR, Germany, Britain and the USA—e.g. Katyusha, Smoke Mortar, T34 Calliope)

- Air-to-ground rockets (unguided) (USSR, Britain, USA and Germany—e.g. RS-82, RP-3, Panzerblitz)

- Remote-controlled bombs (Germany, e.g. Hs 293 or “Fritz X”)

- Napalm bombs (USA, their predecessors were the much weaker German “Flambos”, see page 42)

- Flying bombs (unguided) (Germany, V1, precursor of the guided Cruise Missile)

- Long-range ground-to-ground rockets (Germany, “V2”, precursor of today’s ICBM)

- Jet fighters (Germany, e.g. Me 262, a clearly inferior development by Britain became operational: Gloster Meteor)

- Rocket-propelled fighters (Germany, e.g. Me 163)

- Proximity fuse anti-aircraft shells (USA, VT, a reflected radio echo impulse automatically detonated 10 yards in front of a V1, e.g. in flight)

- Air-to-air rockets (unguided) (Germany, e.g. R4M, contrary to earlier improvisations first air-to-air rocket specifically developed for this purpose)

- Air-to-air rockets (guided) (Germany, wire/radio guided, e.g. Hs 117 H, Kramer X4)

- Ground-to-air rockets (guided) (Germany, in-built targeting camera (already in 1945), Rheinland A)

- Jet-propelled flying-wing fighter bomber (Germany, Ho IX/Go 229, first Jet with light Stealth anti-radar qualities)

- Atom bombs (Germany, especially ignition technology. According to US-Colonel D. L. Putt, chief Technical Services, two German bombs were operational [i.e. presumably two types, uranium+plutonium (Pu)]. The USA mainly researched Pu-type. Surprisingly enough the bomb used over Hiroshima was a uranium type)

The challenges of bombing raids on allied shipping accumulations

The dawn of the remote-control guided bomb arrived in the summer of the year 1943. For a long time German bombers had not only the fighter umbrella to worry about as they approached allied shipping fleets, but also the devastating concentration of fire of the enemy’s anti-aircraft guns, which often numbered into the thousands in the case of very large convoys. The blanket of fire, especially at low and medium altitudes and in daylight, was so intense that the final run to the target was scarcely ever likely to be damage-free. At night visibility was, of course, insufficient to allow for the optimal targeting of the bombs, even with the use of flares to illuminate the enemy convoy.

The birth of remote-controlled bombs

The idea of developing a weapon, which would enable an attacking bomber to maintain a safe distance from an enemy ship or flotilla yet still achieve a direct hit, was thus an attractive one. However, the greater the distance a bomber was to a moving target, the more difficult the targeting process became, since the target object had more time in which to alter its course and evade a torpedo that had been launched, or bombs which were already falling, by means of evasive manoeuvres.

Unless, as if by magic, the bomb replicated the defensive manoeuvres. Therefore, it had to be remote-controlled.

When the time came a British admiral, impressed by this method of attack, described it as “science fiction warfare“.

The joystick and control of the guided missile

German scientists developed two types of remote-controlled bombs. One variant was designed by Dr. Max Kramer of the DVL (Deutsche Versuchsanstalt für Luftfahrt – German Aviation Research Institute) in Berlin and was built by the Ruhrstahl company. The explosive device was given the name of Fritz X.

The „Fritz X“ remote-controlled glide bomb

The bomb had stub wings and a box-shaped control unit. Stability in flight was achieved by means of a gyroscope, and the flight path was adjusted using the elevators and ailerons. These were coupled to a radio receiver, the transmitter for which was located in the bomber. Inside the bomber the bomb-aimer operated a steering device which, in the language of the time, was referred to as a “remote-control device with a mounted lever“. Time and languages change, however, and today it is known in many languages throughout the world by the rather shorter, simpler name of a joystick, albeit in this case the joy might be a one-sided emotion.

The only thing the bomb aimer now had to do—and it was in fact far from being a simple matter— was to align the bomb with the zig-zagging boat until the warhead struck the target and exploded. In order to allow the bomb aimer to monitor the trajectory of the guided missile over a considerable distance—Fritz X was usually dropped from an altitude of between 13,000 feet and 23,000 feet—there was a marker flare in its tail unit, which could be clearly spotted over a distance of several miles.

The Fritz X was a heavy bomb which was developed from the bomb SD-1.400 (the number refers to its weight in kilograms, thus 3,086 lbs). Therefore it could not be self-propelled. This meant that as before the attacking bomber was in the unfavourable position of having to fly over the ship it intended to sink, in order to steer the bomb accurately to the target. Nevertheless the aircraft was able to stay at an altitude at which it could only be attacked by the ship’s heavy anti-aircraft guns, which were far fewer in number than the smaller guns and, in addition, since it was now a smaller, long-range target it would be more difficult to hit.

As an example, an aircraft dropping the Fritz X from an altitude of 18,000 feet, would release the weapon some three miles before the target ship. The radio-controlled freefall bomb would then accelerate to a speed of 950 feet per second (650 mph). At the point of release the pilot would throttle back and reduce speed rapidly by means of the flaps, so that the bomb aimer did not lose sight of the bomb. Since due to inertia the heavy bomb initially flew at the original speed of the aircraft at the moment of release before beginning to fall, the bomb aimer was now above and behind the missile and, therefore, in a good position from which to control it. Incidentally the enemy anti-aircraft gunners would not have anticipated the sudden braking of the bomber, and their fire would temporarily be directed too far ahead of the bomber, exactly where it ought to have been been, based on the aircraft’s previous flight speed up to that point.

The Hs 293: A guided short-range cruise missile

The second weapon of this type was even more technologically advanced. In this case it would be justifiable to refer to it rather as a kind of short-range guided missile than a remote-controlled glide bomb. The Hs 293 was developed by the Henschel company from the SC-500 (1,102 lb) bomb, and was more like a rocket-propelled glider than a bomb. The warhead of both weapons was identical (661 lbs) but the difference in their armour-piercing capability relative to the weight of the bombs was enormous.

In contrast to the much heavier Fritz X this missile was self-propelled, being equipped with a liquid-fuel Walter HWK 109-507 rocket engine. The rocket engine was automatically ignited on launch after safely clearing the aircraft, and accelerated the winged missile in such a way that its flight path lay ahead of the bomber’s. Although the pilot of the launching aircraft did have to reduce its speed, it neither had to brake suddenly, nor actually did it have to fly over the enemy fleet. Given favourable conditions and good visibility this in effect meant that the bomber was in fact able to steer clear of all of the attacked target ship’s potential defences. This constituted a dream scenario for the crew of the German bomber—but a nightmare for the sailors on board the target ship.

The rocket engine ran for approximately ten seconds before burning out, after which time the missile transferred to a glide mode as it maintained its forward momentum. Altogether the flight lasted up to approximately one and a half minutes. As was the case with the Fritz X the elevator and ailerons were actuated by means of a radio link between a Kehl transmitter and a Straßburg receiver. This combination allowed 18 possible frequencies to be used, which meant, effectively, that a maximum of 18 individual missiles could be simultaneously launched by a bomber formation towards an enemy fleet. Further developments in the technology envisaged wire-guided missiles with which to neutralise the jamming attempts by the enemy in respect of the radio frequencies, and even a television monitor control system, neither of which, however, ever became operational. A specific form of wing tip limited the speed of the missile to 820 feet per second (560 mph). However, this should be considered its maximum speed. After it had been launched its speed was some 375 mph. A gyroscope-controlled unit once again provided roll stability and, in addition, dynamic pressure measurement allowed automatic speed-related trimming of the control surfaces. The Hs 293 either had flare markers in the tail unit, or alternatively backward facing flashing lights which were for use during night-time missions.

Aiming and hit rate: remarkable accuracy

Targeting followed exactly the same procedure as applied with the Fritz X. The bomb aimer aligned the light source of the flying bomb with the outline of the enemy ship. The target accuracy was quite remarkable, around sixteen square feet from a range of seven miles. In operational use that translated to a 50% hit probability. These were the kind of figures hitherto only dreamt of. At any rate, although dive bombers could lay claim to an equally impressive strike ratio with their bomb targeting, their missions were in what could almost be termed close combat situations, which were highly dangerous compared with those involving the remote-controlled weapons. The price paid by the dive bombers in the meantime was, however, high.

An attack on an enemy flotilla with hi-tech weapons, which were the stuff of science fiction stories, threatened to revolutionise the German war on ships and shipping, a role which until then had been assigned to dive-bombers and torpedo bombers. But there was a big problem: the launching bomber had to maintain a steady course, to some degree, until the bomb aimer had guided the remote-controlled weapon to the target. For he had to keep sight of the warhead from a relatively predictable flying position, if he hoped to keep control of the bomb. This precluded the bomber from making sharp turns, since it would then be impossible to track the target with a joystick. Thus the only possible successful outcome to a mission using these highly innovative weapons would be when there were no enemy fighter aircraft present. Then, it was still possible, although by the year 1944 at the latest, a trouble-free run to a target over the Normandy landing beaches along the French coast would have been unthinkable.

The beginning of the remote-controlled bombing era

The checkered career of remote-controlled bombs began on 25th August 1943 in the Bay of Biscay on the west coast of France. It was there that allied anti-submarine groups were giving the “wolf packs“ a fearful time along the U-boat routes to and from the German bases in France, particularly La Rochelle. Admiral Dönitz asked the Luftwaffe for urgent assistance against the Royal Navy destroyers and corvettes.

The losses among his U-boat fleet could no longer be sustained.

The first attack with the guided missiles was not a complete success, however. The 14 Dornier Do 217 E-5s of II./KG 100 took off from Istres, some 25 miles north-west of Marseille, escorted by seven Junkers Ju 88 C-6s. They eventually found an enemy flotilla off the north-western tip of Spain. Each of the twin-engined Do 217s were capable of carrying two Hs 293 guided missiles, but for such a long-range mission instead of a second missile they carried an overload fuel tank beneath the port wing.

The destroyer HMS Landguard was damaged by a guided missile which only just missed the ship, detonating in the water beside the bow, and HMS Bideford was also damaged. The other ships escaped the air attack. The sailors in actual fact had no idea what was happening.

Air attack with guided bombs – their narrowly missed target

The same applied to Captain Godfrey Brewer, the captain of the British sloop, HMS Egret. At 14.00 hours on 27th August 1943 he spotted a German bomber formation approaching and counted 21 aircraft. There were actually 18 Do 217 E-5s, again from II./KG 100, consistent with the maximum possible number of frequencies for controlling the Hs 293s.

The enemy formation split into three sections of equal strength.The British anti-aircraft gunners prepared to fire, but the Germans stayed beyond the range of their weapons. Even a heavily armed special flak ship could do nothing. The crews were puzzled as to what the bombers were up to: surely they were going to attack now, were they not?

Mysterious projectiles: unknown threat from the air

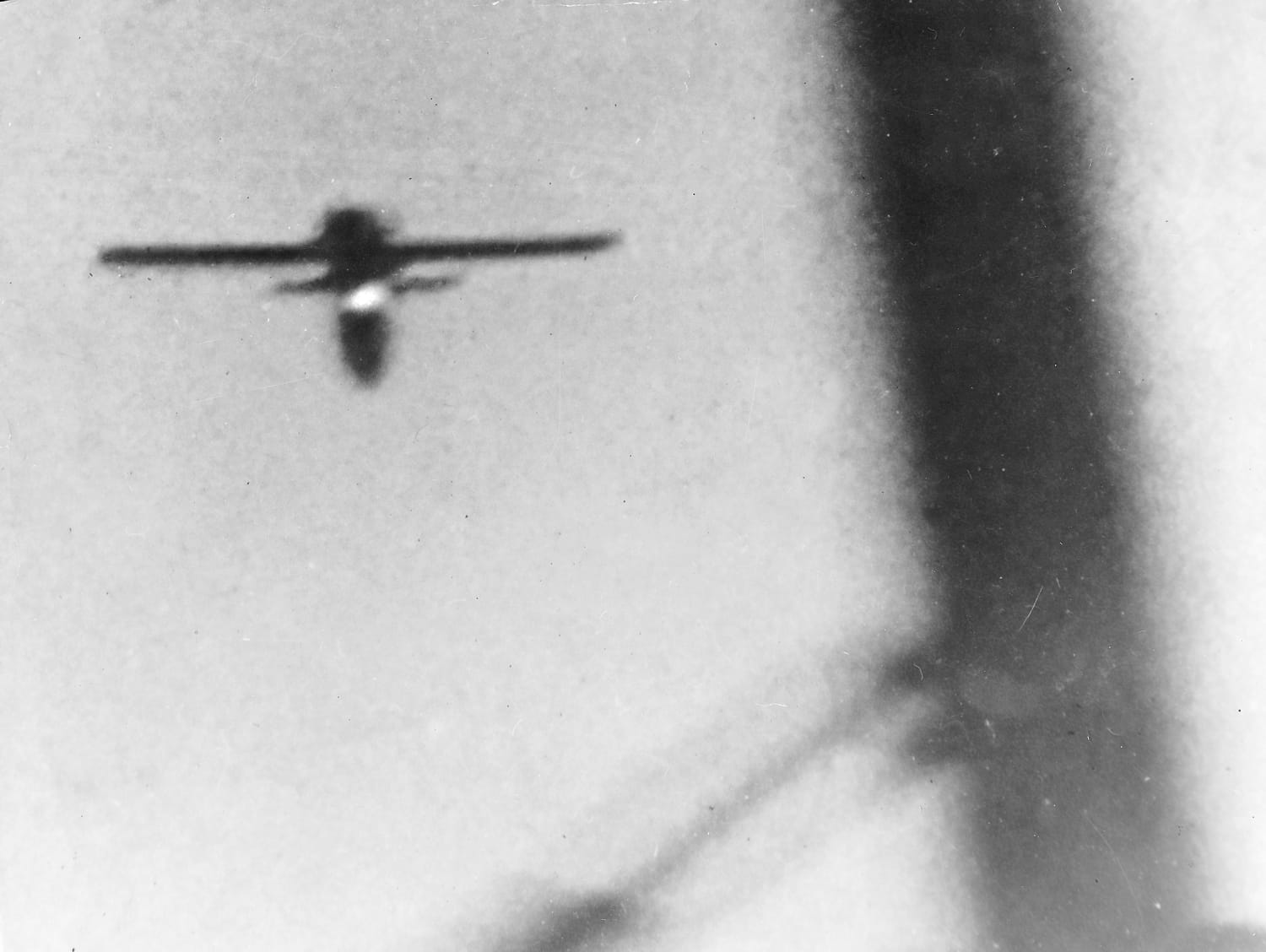

Suddenly small clouds of smoke billowed from below the starboard wings of each of the twin-engined German machines. Something emerged from the smoke which looked almost like a tennis ball after an ace had been served. This object was now tearing away from the aircraft like greased lightning. Suddenly the crew realised that those gadgets were apparently flying straight at them.

The projectiles literally rained down on the Egret. Five of them exploded just in front or just behind the ship: the men up there needed to practise damned harder . The men below could not believe their eyes. The order to fire was given to the anti-aircraft gunners and the Oerlikon rapid-fire guns pounded away at the projectiles. Another one tore past and this time one of the British 2 cm shells hit the rocket or whatever it was, causing it to explode in flight. Hats off to the gunner for a damned good shot!

“Careful, look out! That one’s for us, too. Get out the way, turn away! The damned thing’s following us. Shit! Give us cover!“

It happened incredibly fast: the British sloop was struck by an ear-shattering explosion. It had been directly hit on the aft magazine which housed the depth charges.

Brewer stood on the bridge and stared in disbelief at his burning naval uniform. Then he was struck hard on the head by something. When Brewer came to he found himself overboard, floating in the sea. Nearby the captain could see the keel of his capsized sloop. Apart from him there were another 27 men who survived the devastating explosion, all from the bow or the bridge. A total of 222 naval crewmen lost their lives in the first ever sinking of a ship by remote-controlled weapons in history. In addition HMS Athabaskan was severely damaged. After this incident the British withdrew from the Bay of Biscay. From a German viewpoint their exile signified “mission completed“.

Ebenfalls interessant…

The final kill of the ace of aces, Erich Hartmann, the most successful fighter pilot of all time

Dangerous encounter in the airIn March 1945 a Russian bombing attack on Prague was reported. Hartmann took off with four Me 109s. A Russian formation…

Weiterlesen

Sturmjäger – cuirassiers of the air

Air battle over Germany: the attack on hydrogenation plants and aircraft factoriesIn the early hours of the morning of 7th July 1944 756 B-17 Flying…

Weiterlesen

That’s how historic air battles get botched by Hollywood

Time and again the ignorance and nonchalance with which even highly renowned directors simply ignore historic details is fascinating. They do this in spite of…

Weiterlesen