German bombers of the second half of the Second World War

Improved and new German bombers

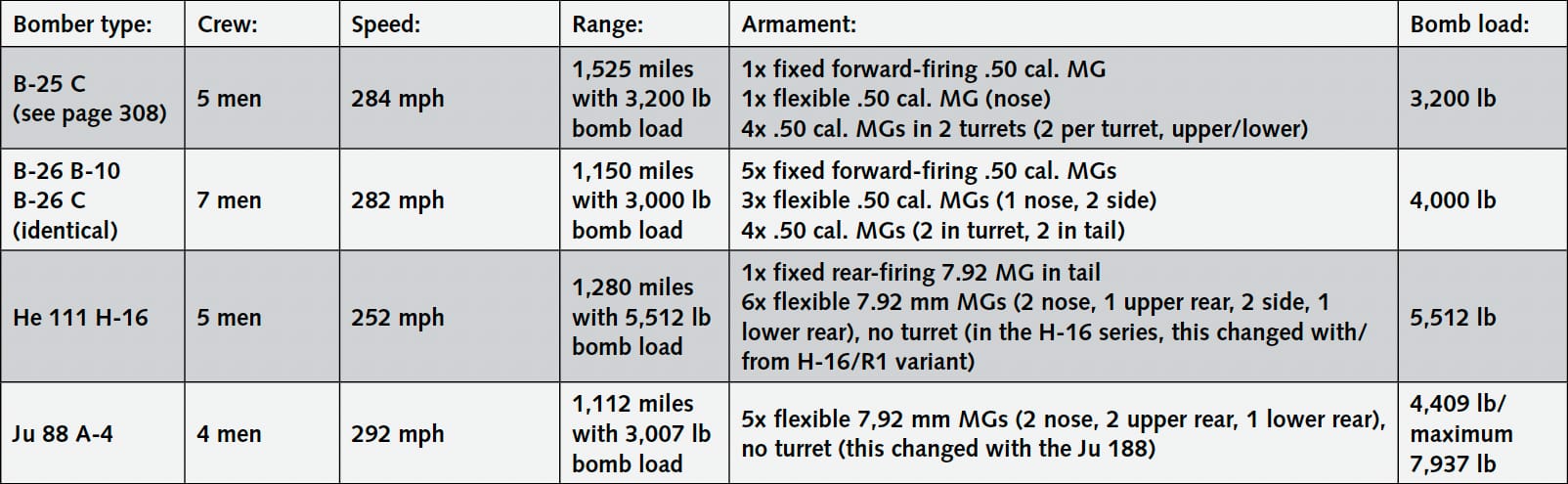

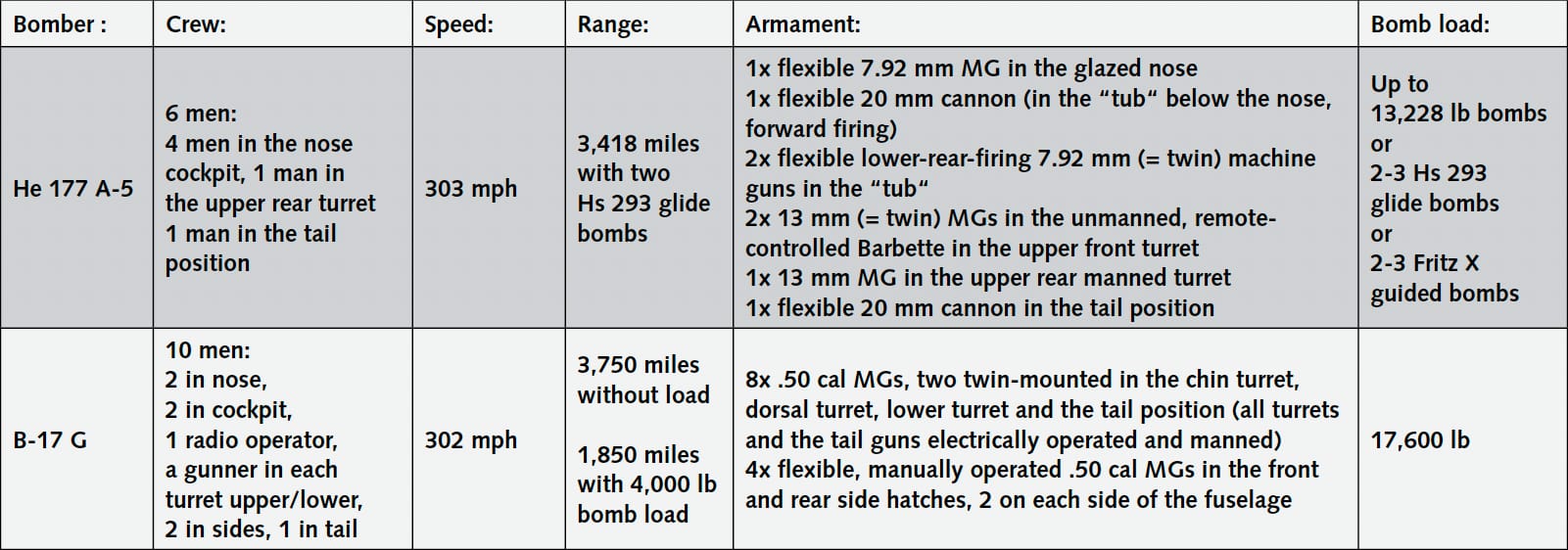

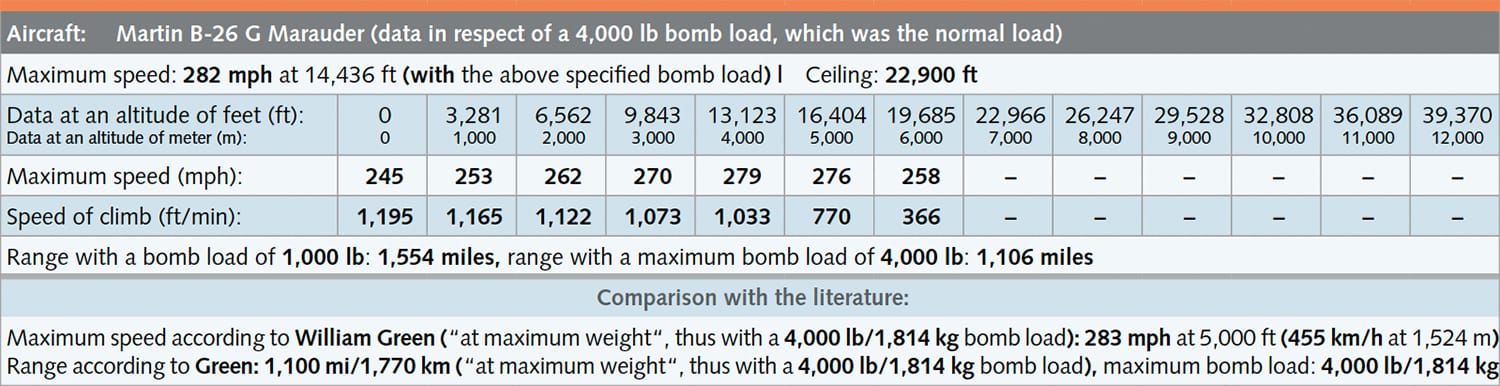

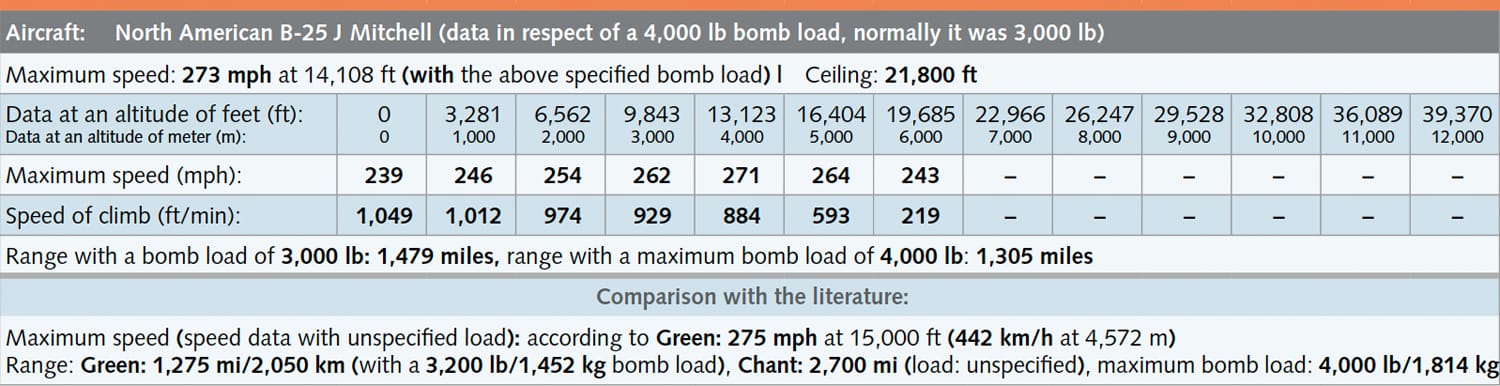

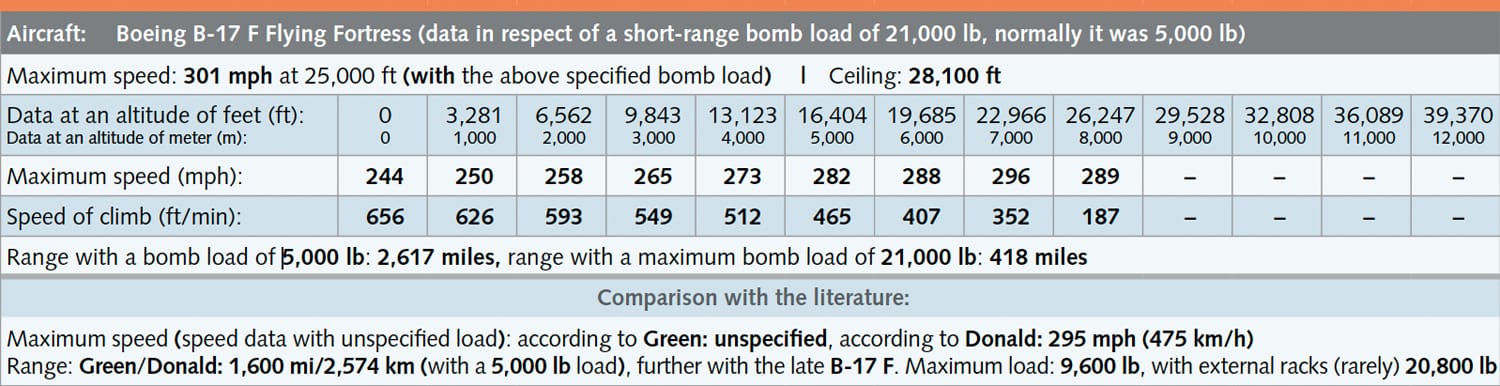

In assessing the performance of the existing German medium-range bombers still being employed in the main against the considerably more modern US models—the Martin B-26 Marauder and the North American B-25 Mitchell—the following comparisons have been made, in respect of the core data only:

Deficits in the defence armament of German bombers

In terms of agility the Ju 88 was still competitive, whereas the He 111 was simply obsolete. The lack of adequate, up-to-date defensive weapons in the German bombers could not be overlooked. In particular, a defensive armament based solely on flexibly-mounted, hand-operated machine guns was no longer viable. The enemy gunners had a much easier time of it with their electrically-operated rotating turrets, which overcame air resistance. The gunner was therefore able to maintain his concentration on the actual targeting without physical exertion.

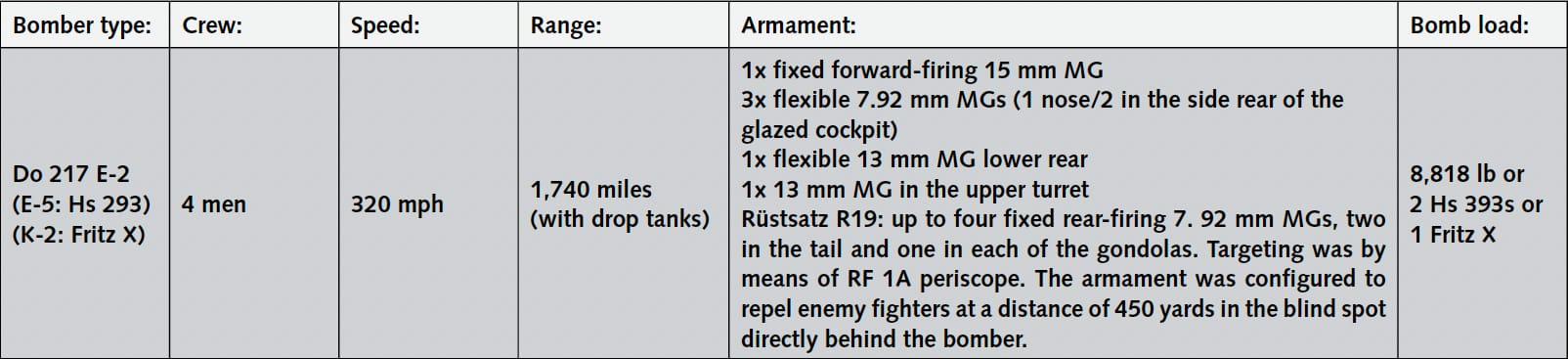

The first German bomber equipped with this technological advance was the successor to the Dornier Do 17. This aircraft was replaced in the year 1941 by the Do 217 E-1, and the subsequent E-2 variant of this excellent bomber was equipped with an electrically-operated machine gun turret at the rear end of the cockpit. As before the crew was concentrated in a single cockpit. With the exception of the He 111 this design feature was characteristic of all the German medium-range bombers. The K-2 variant and the following versions of variant the Dornier Do 217 received a fully glazed nose which did not in fact constitute much of an improvement.

Fields of application of the Dornier Do 217

The Dornier Do 217s gave a very good account of themselves and by Spring 1941 the E variant was already being employed by II. Gruppe of Kampfgeschwader 40 against ships. Kampfgeschwader 2 also flew the Do 217 against British targets. However, since the dive qualities of this potent bomber were unsatisfactory—this was the single technical feature in which it did not come up to scratch—the Reich Ministry of Aviation was never really convinced about the aircraft. The obsession with the idea that every German bomber should be usable as a dive bomber would lead to the creation of the most fantastic hybrids.

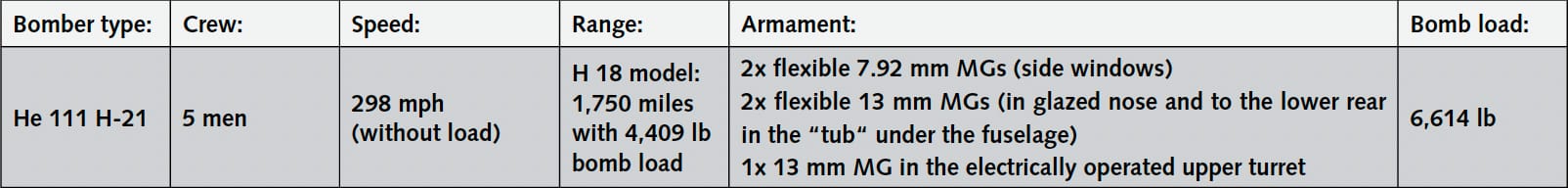

Upgrade of the Heinkel He 111: introduction of a turret

The obsolete Heinkel He 111 was also equipped with a rotating turret. With the H-16/R1 variant and eventually the He 111 H-20 (from the year 1944) the defensive armament of this aircraft, which was still elegantly streamlined although way behind in terms of performance, was considerably strengthened. The He 111 continued flying until the end of the war and still held its own on the Eastern Front, but the newer Dornier and Junkers models were vastly superior to the He 111 H-20.

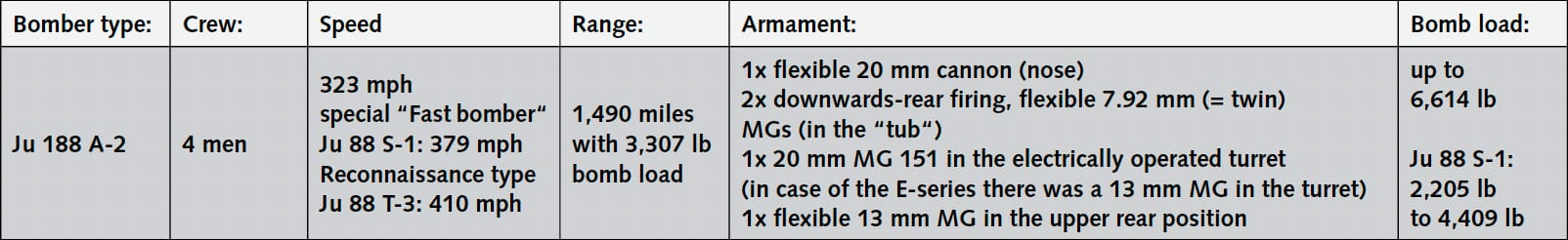

Ju 188 vs. Ju 88: Improvements in speed and climbing ability

The most elegant improvement, however, concerned the versatile, all-purpose German bomber, the Junkers Ju 88. This Luftwaffe war horse evolved into the Junkers Ju 188. The Ju 188 preserved all the good qualities of its predecessor but was faster and had considerably better climbing performance. Furthermore the Ju 188 had the better armament. With good fortune a capable pilot could escape a fighter and, although the same applied to other bombers, the chances of that happening in a Ju 188 were better.

Originally the requirement was for an aircraft with dive-bombing capability and the Ju 188 was designed with that in mind. However, when the first Ju 188s were finally delivered in May 1943 in the A-1 and E-1 variant the new remote-controlled bombs made dive-bombing capability unnecessary. Already in the case of the A-2 model dive brakes as a standard fitment had thus been dispensed with.

The A-series and the E-series had different engines in order to avoid supply constraints, so that the aircraft were either fitted with the Jumo 213 A-1 (A-series) or the BMW 801 D-2 or G-2 (E-series) without requiring any complex conversion measures. Both engines produced some 1,750 bhp and 1,730 bhp respectively. A further distinguishing feature concerned the armament in the electrically operated dorsal turret. The A-series generally used the MG 151 20 mm cannon in this gun position, whereas the E-series was usually equipped with a 13 mm MG 131 in this position, both of which were outstanding weapons.

Junkers Ju 188: the Luftwaffe’s best medium bomber in the Second World War

During the course of the war only 1,076 of these aircraft were produced compared with roughly 15,000 of the Ju 88s. The Ju 188 could be considered the best medium-range Luftwaffe bomber of the Second World War. From the very beginning it had a marvellous reputation among the bomber crews.

Heinkel He 177: an aircraft with a controversial reputation

The Luftwaffe bomber with perhaps the most chequered history was one saddled with an unenviable reputation. It was an aircraft that was allegedly deemed to be more dangerous to its own crew than it was to the enemy.

At the beginning of its career this technologically highly sophisticated heavy bomber to a certain extent justified this stigma. That the technical problems would in the end be largely ironed out was another matter. For completely different reasons the crews hardly ever had the opportunity of flying successful missions and belying the aircraft’s poor reputation.

The poor reputation came about through a combination of two unfortunate circumstances, one of which was simply unnecessary and the other rectifiable over time—which Germany no longer had.

Priorities and resources: the hurdles of bomber production

When the German Reich began to equip its bomber fleets, his planners in the year 1936 made a persuasive case to Hermann Göring of an urgent requirement for Germany to develop heavy strategic bombers, and demanded they began producing them. Hitler had only ever asked him the number of bombers they produced, not their size, he replied.

The production of four-engined heavy bombers in Germany therefore foundered on the reluctance of the Commander-in-Chief of the Luftwaffe, the then Generaloberst Hermann Göring, to risk representing the legitimate interests of the Luftwaffe to the Führer. That, however, only tells half of the story. Germany in fact needed to be far more frugal with its raw materials and industrial capability than Britain (which had American support), the USA and also the USSR. Above all, the inter-continental perspective of Great Britain and the USA as island states, therefore, as well as their abundant natural resources, made things so much easier for them to set for themselves different priorities. In the year 1936 who could have imagined the devastating effects this would one day have on Germany’s cities?

Requirements for the German strategic bomber

When it began to dawn on them, they did at long last pave the way for the development of a strategic German bomber. It was to be a fast, four-engined, long-range bomber, capable of carrying a heavy bomb load and able to dive at medium angles, which they later raised to 60°. A jack-of-all-trades, indeed, if ever there was one.

At the beginning of 1939 the first prototype of the Heinkel He 177 Greif (Griffin) was ready: a truly revolutionary aircraft. To reduce aerodynamic drag and achieve the manoeuvrability for the required diving capability the four engines were housed in two nacelles. Both engines which were coupled thus drove one shared propeller shaft. The four-blade airscrews were correspondingly massive. The visible presence of two propellers therefore actually drove what appeared to be a twin-engined aircraft with the power of a four-engined bomber, but against the reduced drag of only two nacelles. In addition, the two propellers rotated in opposite directions, the port twin-engine ran anti-clockwise, and the starboard twin-engine clockwise. That was also an innovative idea.

Everything was done to improve the aerodynamics of the aircraft. Instead of the otherwise usual radiators required for cooling, steam condensers were used to reduce drag. A fully glazed, rounded nose meant they could dispense with the raised cockpit on the fuselage, which was a feature of the Boeing B 17, and remote-controlled, unmanned gun turrets could be kept considerably flatter than rotating turrets, in which the shoulders and head of the gunner had to be accommodated.

Improvements and challenges in detail

However, the devil was in the detail and in the unrealistically excessive demands of the Reich Ministry of Aviation. In order to give such a large aircraft a dive-bombing capability (and what would be the point of such an aerobatic manoeuvre with a strategic bomber?) the airframe and the wing roots needed strengthening. That meant an increase in weight which deprived the bomber of its skilfully designed advantage in speed. Apart from that it would not work, because in design terms it was just not possible. To expose a wingspan such as that of the He 177 to real diving and in particular pulling out of the dive, would be tantamount to going into a paratroop mission equipped with an umbrella. Whatever the brilliance of the aircraft designers there were incontrovertible laws of physics, no matter who was pulling the strings.

In addition, there were basic flaws in the design. Some, it must be said, bordered on the amateurish. The whole cooling system was unreliable and the oil pipes leaked: it was a recipe for trouble.

The inglorious career of the first series

What followed was the inglorious career of the first pre-production models as the Luftwaffe’s flying “cigarette lighters“. Fire in the engines became such a frequent occurrence that the enemy did not even take the trouble to shoot down the German super bomber. The contra-rotating engines caused uncontrollable sideways swerving on take-off, unless they were perfectly synchronised.

From October 1942 the first improvements were brought to bear with the He 177 A-3 variant. From February 1943 the new Daimler-Benz DB-610 engine was available. This time the technicians finally did their homework, analysed the fires and rectified the shortcomings.

Fulfilment of the original promise

The He 177 A-5 now finally delivered what the original design had promised. However, as is so often the case with a bad reputation, the psychological damage, unlike the technology, proved irreparable.

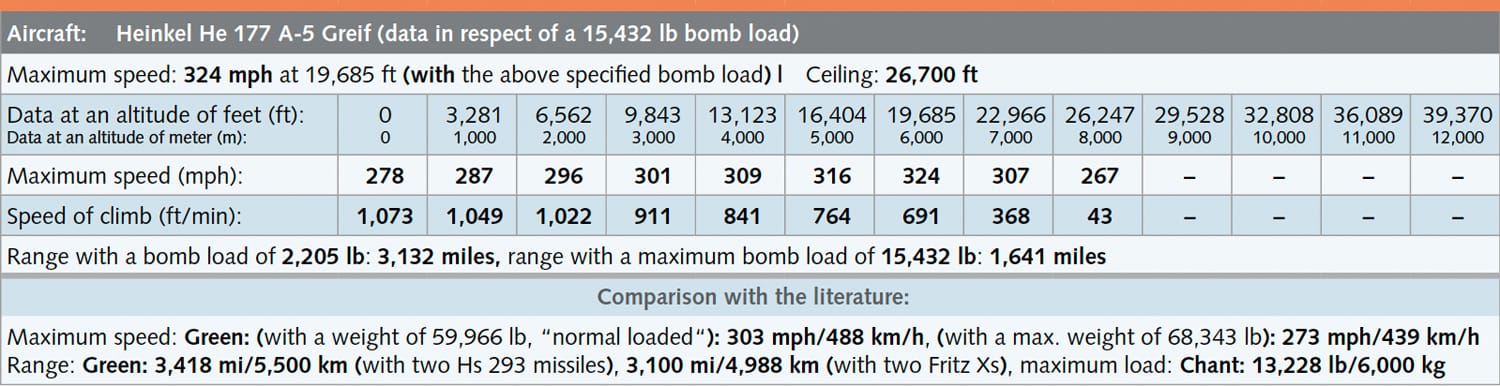

Ultimately a total of 565 of the He 177 A-5s were produced. Many were employed in night-time attacks over Britain. The pilots used the aircraft’s limited dive qualities to their advantage, although at angles greater than 40° it became dangerous. However, from an altitude of 29,500 feet, flying at such an angle would enable the aircraft to attain speeds of up to 435 mph: too fast for the majority of the British nightfighters. The losses due to enemy action were gratifyingly few in number.

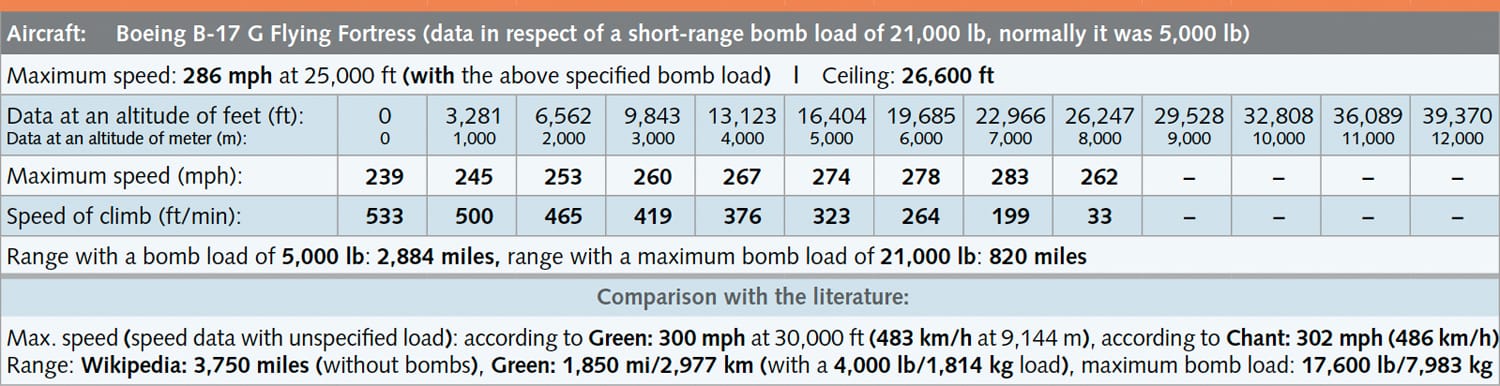

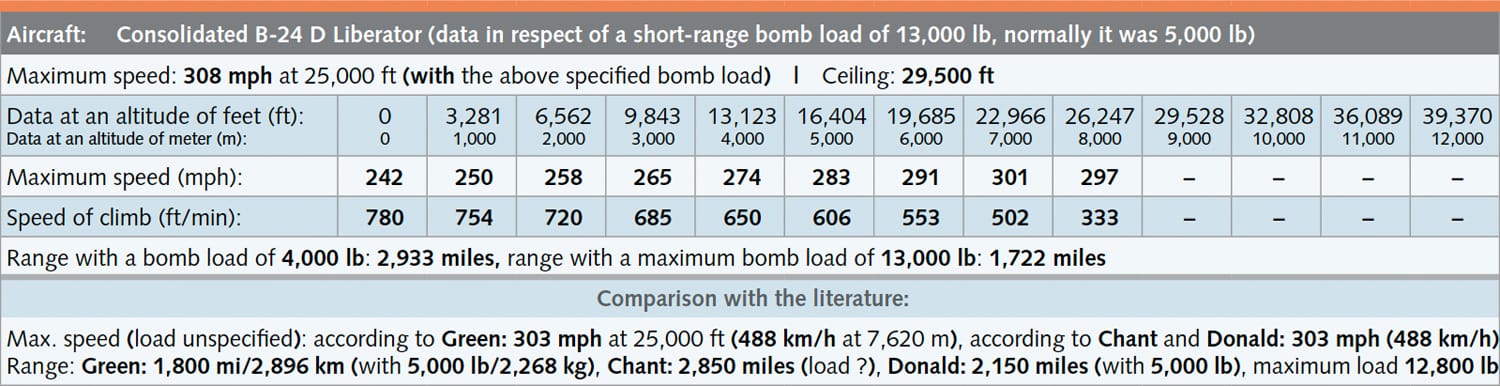

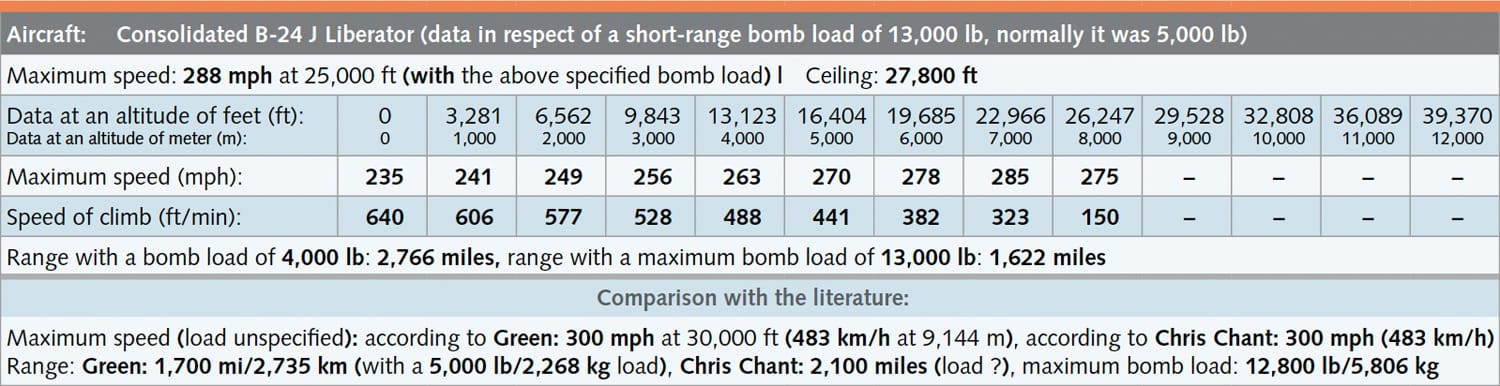

The normal maximum speed at level flight with its bomb load at an altitude of 20,000 feet, however, amounted to “only“ 303 mph. This compared favourably to the speed of a B-17 G (302 mph) or a B-24 J (300 mph) both of which housed their four engines in four nacelles, regardless of the drag.

Enthusiasm despite a problematic history

However, the opinion of certain German crew members casts doubts on a judgement based on speed comparison alone, suggesting that the sole German long-range strategic bomber had evidently been unjustly maligned.

“Although the He 177 had a troubled development history and has received a bad press from historians, prisoners from these particular machines spoke highly of them. High altitude performance was good, with speeds of 600-650 km/h [373-404 mph] ‘easily attained‘; the He 177 A-3 was rated ‘more manoeuvrable than any other GAF [German Air Force, Luftwaffe] bomber‘ “ and: “Both crews are most enthusiastic about the engines, which appear to function smoothly and efficiently over incredibly long journeys. The disengaging (to save fuel) and re-engaging of the motors now takes place without any risk of fire, a tendency known to have been rife when the motors were first used“.

(Attention is drawn to the fact that the cupola cover of the front remote-controlled Barbette turret lay on the wing in the original photo. Evidently the machine guns were just being serviced. However, as the aspect of the picture was ideal for illustrating the state-of-the-art armament, the author took the liberty of using a photomontage technique to transfer the cupola to a closed position, which of course is not legitimate in the case of original photographs. For this the author offers his unreserved apology and asks for understanding concerning his intentions in doing so. At least this manipulation shall be mentioned clearly).

Night attacks: The method of the He 177 crews

Despite the heavy defensive armament daytime missions without their own fighter escort was no less dangerous for the He 177s than for the American Flying Fortresses. The crews of the He 177s therefore developed a method for attacking shipping targets at night-time which was relatively free of risk. However, as the enemy developed its increasingly potent deployment of nightfighters this also became a correspondingly more dangerous activity.

One of the bombers or several (in the case of large-scale attacks) would launch flares attached to parachutes on one side of the enemy fleet or convoy. These would then float slowly down, bathing the ships in a pale light, against which the ships’ silhouettes could be clearly seen. The enemy fighter pilots and anti-aircraft gunners would then find their attention being automatically directed towards the lights. Until the other formation of He 177s launched their glide bombs from the other side of the ships at a safe distance of six to eight or so miles, at any rate.

Reasons for the lack of success of the German long-range bombers

Why were the German long-range bombers denied a similar success to that achieved by the allied bomber formations? The answer is a simple one and has nothing to do with technology or tactical errors.

• A lack of industrial capacity and natural resources meant that the development of a huge strategic bomber fleet, such as the Americans and British were able to deploy, was never possible.

• Even if a substantially higher number of He 177s had been available earlier, by day the Germans would have been unable to provide them with a sufficiently strong fighter protection.

• And in particular: only 400 or so of these bombers had consumed one eighth of the entire monthly production of German aviation fuel in the year 1943. By 1944 the shortage of fuel was reaching crisis point.

Eventually, from the middle of 1944 the majority of the German long-range bombers were forced to remain on the ground: there was simply not enough fuel left to go round. The allied fighter bombers did the rest.

Large bombers such as the He 177 could not simply be hidden beneath trees. A glance at the photo above right clearly shows the effect of an American low-level attack on the airfield at Schwäbisch Hall, north-east of Stuttgart.

Ebenfalls interessant…

The final kill of the ace of aces, Erich Hartmann, the most successful fighter pilot of all time

Dangerous encounter in the air In March 1945 a Russian bombing attack on Prague was reported. Hartmann took off with four Me 109s. A Russian…

Weiterlesen

Sturmjäger – cuirassiers of the air

Air battle over Germany: the attack on hydrogenation plants and aircraft factories In the early hours of the morning of 7th July 1944 756 B-17…

Weiterlesen

That’s how historic air battles get botched by Hollywood

Time and again the ignorance and nonchalance with which even highly renowned directors simply ignore historic details is fascinating. They do this in spite of…

Weiterlesen